May 12, 2021

On May 6, Free Press issued a new report titled “Price Too High and Rising: The Facts About America’s Broadband Affordability Gap,” that found:

- U.S. broadband prices are stable;

- More U.S. families are purchasing broadband;

- Many U.S. families are upgrading the quality of broadband in their homes (i.e., faster speeds, higher bandwidth allowances);

- More of this upgraded broadband is fiber to the home (FTTH), and;

- When compared to other high-wage countries, U.S. broadband is similarly priced.

Rather than celebrating this good news, Free Press finds it odious.

Why?

Free Press’ Stats Point to Good News on Consumer Pricing

Instead of embracing USTelecom’s report showing that broadband prices are declining for consumers, Free Press seeks to refute it using the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data to bolster its claims. But the data it presents does not support its contrary position that prices are rising. Rather, BLS data show price declines relative to inflation. Let’s dive in:

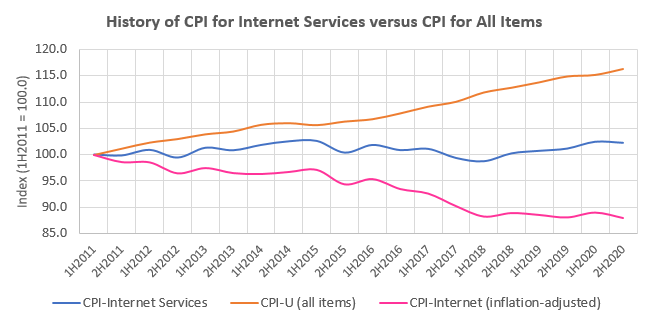

First, (at Figure 14), Free Press finds BLS’ flagship series, the Consumer Price Index (CPI), shows that over the 2012 to 2020 period, prices for Internet access services have been flat in nominal terms, and decreased by 12% in real (inflation-adjusted) terms. Take a look:

Sources: CPI-Internet Services, CPI-U (all items)

Instead of celebrating this undeniably positive statistic for Internet customers, the report chooses to note only that prices declined during Title II broadband regulation, and ignores that over the entire decade broadband prices have been declining relative to other prices – regardless of the regulatory scheme.

Not finding BLS’ CPI supportive of its line that broadband prices are increasing, the report then claims (without traceable citation) that raw data that it has mined out of the database that BLS assembles on consumer expenditures supports its view that broadband prices are increasing. Even if these data were reliable, and we doubt this because BLS itself does not consider such detailed data reliable or accurate, average expenditure figures collected are not the same as price. Average household expenditures rise when more households subscribe to broadband or families upgrade to higher quality broadband – both of which were occurring during the 2013 to 2019 period examined in the report.

Families Choosing Higher Speed Connections is Bad?

Oddly, the report then attacks the families that have chosen to purchase higher capability broadband services, and especially the families that have chosen FTTH services – deriding these upgraders as purchasers of unneeded “Cadillac” technologies (p. 14-15). The report also expresses displeasure that broadband providers have responded to this burgeoning consumer demand for higher speed broadband services (perhaps intensified due to the COVID pandemic) by competing for customers and lowering prices. The report’s solution to this demonstration of market competition (old enough to remember when that was a good thing) and customer demand? Strike FTTH plans and prices from the data it pulls from the FCC’s URS because removing this data is necessary to support the intended narrative of rising broadband prices.

Making Real Comparisons—Americans Win

As a last gasp, the report tries to revive the discredited claim that broadband prices are less expensive abroad than in the U.S. Of course, in order to do this, the analysis must disregard that:

- High quality networks are more extensively deployed in the U.S. than abroad;

- More U.S. customers purchase 100 Mbps or gigabit services here than abroad; and

- Costs to deploy networks in the U.S. are higher than abroad due to lower population densities and higher wages.

When these differences are accounted for (see FCC 2020 Communications Marketplace Report paras. 299-300 and Appendix G, finding the U.S. ranked second in pricing) and OTI’s Cost of Connectivity study p. 38), U.S. broadband prices closely match the prices charged abroad.

Finally, in a misguided attempt to distract from these (very inconvenient) facts, the report advances the argument that U.S. broadband prices should be falling as fast as computer prices because both are sold in “technology consumer product markets” (p. 6 and note 8).

This argument ignores the fact that U.S. computer manufacturing has been outsourced to low-wage countries while the telecom industry, with its American work force that builds broadband in the U.S., continues to provide high-wage jobs to nearly 700,000 employees.

So why is Free Press aggrieved? Market facts suggest broadband prices are declining, the quality of services offered by U.S. ISPs and purchased by American families has been continually improving, and U.S. networks are technologically superior to those abroad—and with comparable pricing.

One guess? These facts could well undermine Free Press’ call for municipal broadband, but inconvenient facts are true nonetheless.